BRICK – The local environmental organization, Save Barnegat Bay, runs an annual student grant program that provides a hands-on learning opportunity for undergraduate students who are chosen to conduct field research.

The students normally have a live presentation of their findings, but due to the coronavirus health crisis, they recently presented their research in a Zoom meeting format.

Save Barnegat Bay and its collaborating partners offer a $1,000 grant to each accepted team project student and $1,500 to each accepted independent project student.

Executive Director of Save Barnegat Bay Britta Wenzel said the grant program was started in 2007 by the late Paul “Pete” McLain, a wildlife biologist and conservationist who had a vision and a passion for the conservation of Barnegat Bay.

This year eight students were chosen as grant recipients: three who studied the Sedge Island Marine Conservation Zone behind Island Beach State Park to look at the biodiversity, and five students who studied the water quality in Toms River.

In the first of two team presentations, Jason Kelsey, who is an instructor at MATES (Marine Academy of Technology and Environmental Science), mentored the Sedge Island team. He said they have been studying the area for 10 years and said that having a long-term data set was one of the goals of the project.

The three-student team included Kate Killian, who is a student at Stevens Institute of Technology and is studying naval engineering; Brady Nichols, who attends Bowdoin College and is studying biology; and Sarah Quigley, who attends Berry College where she is studying biochemistry.

Normally, the team does ten non-consecutive days of sampling, and they look at areas in the conservation zone and areas right outside the conservation zone.

Tice’s Shoal, which is a popular spot for boaters to congregate, was their focus for the outside of the conservation zone.

While recreational activities are allowed in both zones, such as birding, kayaking and recreational fishing, commercial fishing and the use of personal watercraft are not allowed in the Sedge Island Marine Conservation Zone, Brady Nichols explained.

The Conservation Zone makes up about 2 percent of Barnegat Bay, he added.

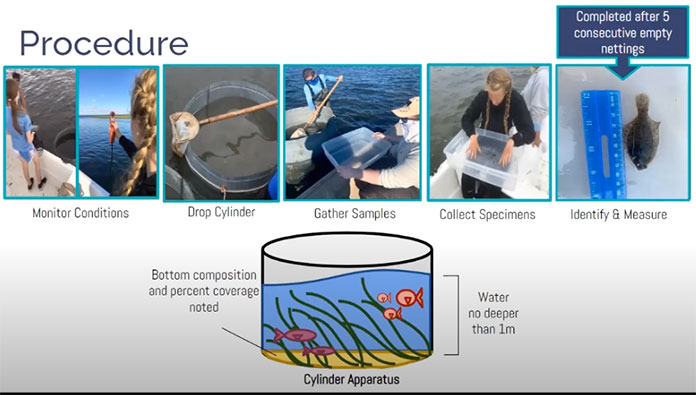

Each day of the study began with choosing a site, when the team would gather information about the area, such as the time, GPS location, weather, wind velocity, water depth, tidal flow, current, dissolved oxygen, salinity and water temperature.

They would then use a one-meter tall cylinder apparatus and drop it onto the substrate and noted percent coverage and bottom composition type. The team gathered samples and scooped them into sorting bins where they identified and measured the collected specimens.

For each sample day, the students did two cylinder drops at each type of substrate location at Sedge and six at Tice’s to make sure they were getting representative examples of what was in the area. While comparing this year’s data to previous years it is important to note that they did about half the normal cylinder drops due to COVID-19 restrictions.

The six most prevalent species at Sedge are shore shrimp, sand shrimp, Atlantic silverside, blue crab, black-fingered mud crab and four-spined stickleback.

Species population trends over the past ten years show a general increase in shore shrimp and a general decrease in sand shrimp. Silverside populations are highly variable because sometimes researchers can stumble across an entire school of them or not, the students explained.

The stickleback have been steadily decreasing over the past five years. The crab population is about the same.

There were no significant differences between salinity, water temperature and dissolved oxygen at the two sites, although fewer species were found at Tice’s.

Out of the five days at Tice’s when the group did 30 cylinder drops, only 14 total species were collected. At Sedge, some 2,000 were collected, said Sarah Quigley, which shows the population is affected by the boat traffic at Tice’s.

The team took questions from the public after the presentation. One viewer asked why Tice’s was chosen as a comparison site. Kelsey said the team usually has access to a NJDEP Division of Fish & Wildlife boat, but due to State COVID policies, the boat was not available.

The team had to use a smaller Jon boat which is a short-range craft that could carry the equipment while the researchers waded or swam out beside the boat. Tice’s is close to shore, he said.

Reading live questions off FaceBook, Wenzel said “the burning question from most members of the public… is ‘What does that mean to us?’”

By comparing and maintaining the data from the conservation and non-conservation zones, the team wanted to see if the conservation zone is doing its job in protecting organisms, and what impact the non-conservation zone has.

“Tice’s Shoal is really disturbed – it has a lot of boat activity all the time,” said Kate Killian. “We wanted to see how much human activity impacts the Barnegat Bay, and it really does have an impact.”

Next week in part 2, The Brick Times will report on the findings of the Toms River water quality team.