The traditional thinking when it comes to the history of the American Revolution is that it was won on land by George Washington and his army. We know the stories of Bunker Hill, Long Island, Trenton, Princeton, Monmouth, Yorktown, and more.

But there’s another view too: that the war was won on the seas – and it wasn’t based on a military strategy, but an economic one. Here’s the story – and Toms River’s role in it.

One Sailor, Two Soldiers

On the eve of the fight for independence, Britain had amassed a military power second to none in the history of mankind: almost 50,000 soldiers – a staggering number in the eighteenth century. By 1763, they had vanquished the French from most of North America – greatly expanding its empire inland far beyond the original colonies nestled along the coast. But it was a long way from home and the only way to get to America was by sea. From this perspective, as the historian Donald Shomette has written, the “American Revolution was by any standard a truly maritime war.” So it would be a struggle on the seas – up and down America’s coast – that would be critical. In the middle of this was New Jersey – and in the middle of New Jersey was Toms River.

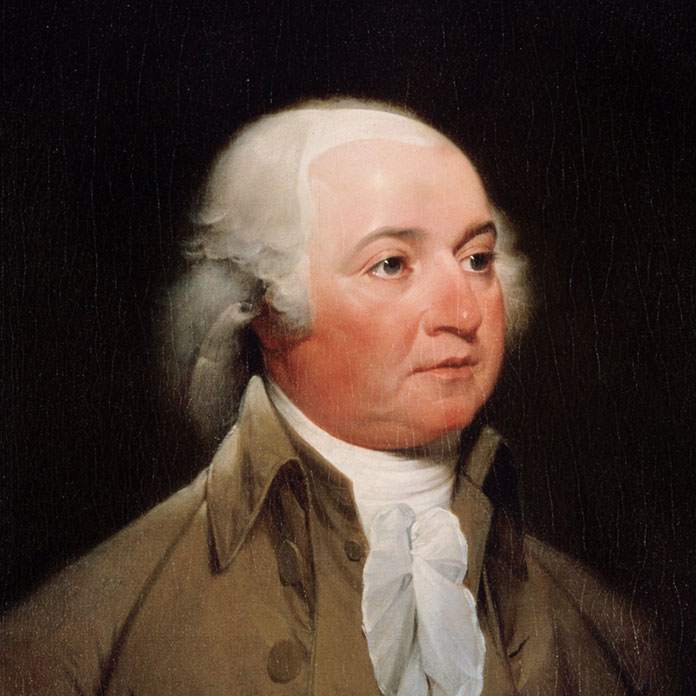

It was not Washington, the general, but of all people, that bookish, Harvard educated lawyer, John Adams, who recognized the seas’ significance. To the Continental Congress, he wrote: “A navy is our natural and only defense.” To Dr. Benjamin Rush, he famously wrote: “If I could have my will, there should not be the least obstruction of navigation, commerce, or privateering because I firmly believe that one sailor will do us more good than two soldiers.”

But privateering? It was an old maritime activity used by European powers going back hundreds of years. Privateering was the use of privately owned vessels to wage war on the seas. Enemy ships were captured and their cargoes confiscated and then sold. Enormous profits could be obtained.

During the years before 1776, both English and colonial vessels would cruise the ocean waters in search of French, Spanish, Dutch, and Portuguese ships. For Americans, when war with England came, privateering was nothing new. In March 1776 – before independence was declared – the Continental Congress resolved to permit the outfitting of privateers – “armed vessels” to prey on the “enemies of the United Colonies.” Adams roundly supported the move. This for-profit, private activity would support the war effort – but it was just one part of a larger effort.

In 1775, Adams also had urged the creation of an official American fleet. On October 13th, the Continental Congress approved of two ships – it had authorized a navy. Adams was appointed a naval commissioner. He knew nothing of warfare by sea – but he studied and made himself an expert.

Eleven states also created their own state navies. Two states did not – Delaware and New Jersey. Since it would take months or years to build these publicly financed enterprises, it fell upon the privateers to lead the way.

The Strategy On The Seas

Since it was all but impossible to take on the mighty British Navy one-on-one, the Americans fought a maritime economic war. The Continental Navy, the state navies, and the privateers – in a three-fold manner – regularly damaged the British by preying upon their commerce and interdicting their supply lines to the mainland. It was Adams who strategized that the Americans should wear down the enemy and make the war economically difficult for them.

It worked. During the first two years of the war, Lloyd’s of London estimated that American privateers captured five times as many British ships as taken by the Royal Navy. As the author Arthur Pierce has noted, American privateers made a “monumental contribution to victory.” British maritime insurance doubled in the first two years of the war. From 1776 to 1782, 1,200 enemy ships were captured or sunk. Privateers captured 16,000 prisoners (while the Continental Army captured another 20,000).

And American privateering was not just off our coast. It stretched to the Baltic Sea. When France entered the war on the American side, maritime travel for the British worsened.

Off the coast of New Jersey, it was guerilla warfare on the seas. Surprise, hit and run, capture of enemy vessels, and the sale of cargoes. And in the midst of all of this was the small coastal hamlet of Toms River. Once again, our town would play a pivotal role in the war for independence – but this time, it was not on land, but on the sea.

It Was All About Geography

An early record from the Continental Congress helps set the story. When the British took New York after their victorious campaign in the fall of 1776, the military landscape changed. No longer was the war for independence isolated in New England. Now, it was a continental struggle with the coast – home to the major population centers even then in the eighteenth century – center stage.

The British occupied the port city of New York. The Americans controlled the port city of Philadelphia. In between the two was New Jersey which provided access to the Delaware River and Philadelphia – home of the fledgling Patriot effort, the Continental Congress – less than 120 miles south of the entrance to New York harbor.

The Jersey coast was now of significant importance. Privateering interests in Philadelphia recognized this. The intricacies of the shifting coastal waters and many tricky to navigate inlets loomed. Included amongst these was what was known as “Cranberry Inlet” – a narrow, shallow opening between the Atlantic Ocean and Barnegat Bay and Toms River. It gave easy access to small vessels, but not Britain’s large men-of-war.

On November 1, 1776, the Marine Committee of the Continental Congress (which Adams was a member) ordered one Elisha Warner, captain of a fast-moving Patriot sloop – the “Fly” – to stake out the coast of Shrewsbury so as to “see every vessel that goes in or out” of New York bay. The Committee believed these vessels would be transport and storage ships supplying the British.

Warner was ordered to use an experienced pilot, and if pursued by a vessel of force, to run inshore, into Toms River, via the inlet, or some other convenient location. He was also told to “keep an especial look out for all vessels inward or outward bound and whenever you discover any give chase, make prizes of many as possible, and as fast as you take ‘em send them to this port {Philadelphia}, unless you hear men-of-war take station at our {Delaware} Capes, and in that case send them into Toms River, Egg Harbor, or any other safe place.”

Thus, at a very early stage of the war – before the battles at Trenton, Princeton, or Monmouth – Toms River was central to the Patriot effort. But it would not be on land. It would be on the seas.

Next In This Month In History: 1822 – Toms River 200 Years Ago

Coming Up Soon In This Month In History: Toms River and the many privateering and naval battles of the late 1770s help turn the tide in the struggle for independence

SOURCES: John Adams by David McCullough, Simon & Schuster, 2001; Smuggler’s Woods by Arthur Pierce, Rutgers College, 1960; Privateers of the Revolution, Donald Shomette, Schiffer Publishing, 2016

J. Mark Mutter is the retired Toms River Clerk. He served as a member of the Dover Township Committee and as Mayor in 1993 and 2000. He chaired the Township’s 225-year anniversary committee in 1992 and its 250-year anniversary committee in 2017, and its 200-year Constitution Bi-Centennial Committee in 1987. He is writing a book on the history of Toms River.