BRICK – Should a portion of property taxes paid by waterfront homeowners be used to dredge lagoons that have become too shallow for boating?

Some waterfront residents who live on Lagoon Drive West and Lagoon Drive East in Nejecho Beach said since they pay higher taxes, that perhaps some of that money could be used to dredge areas that have become shoaled in, causing damage to boats and injuries to people from sudden grounding.

Residents of a neighborhood off Mantoloking Road came to a recent Township Council meeting to ask for help. Their lagoon entrance, measuring some 50 by 100 feet, was damaged by Superstorm Sandy and has become unnavigable.

Norm Gross of Lagoon Drive West said that the shoaled entrance has also affected business in town since bulkheading contractors are unable to get their equipment into the lagoon. The rest of the lagoon is perfect, he said.

“There are 25 or 26 homes on the lagoon who pay 30 percent more taxes because we’re on the water,” Gross said. “I want to be on the water and I want to run my boat in and out safely.”

Gross said last year he witnessed some 15 to 20 private boats who were sightseeing and ran aground at the entrance, many damaging their propellers, resulting in thousands of dollars in damage.

He said one of his neighbors had sustained a deep cut on his head and injured his shoulder after his boat suddenly hit bottom.

Gross said he has been in contact with township engineer Elissa Commins, who is the coordinator for the Army Corps of Engineers (ACE).

“I bothered her for a year and a half with phone calls and emails, and we never made the list with the Army Corps of Engineers,” he said.

Gross was referring to the Department of Transportation Maritime Resource, which had set aside funds to pay for dredging projects after Sandy.

Business Administrator Joanne Bergin said that the township has been lobbying the DOT Maritime Resource to “keep their word and come in, after Sandy, and do all these dredge projects which are absolutely necessary, and then they ran out of money and stopped,” she said.

She said the township has pushed for the Army Corps to repair some of the smaller lagoons while they have already mobilized and are working on larger projects.

Mayor John G. Ducey said that the township would provide engineering, permitting and a hydrological survey for the dredging at cost of about $60,000, but the lagoon front homeowners would be responsible for dredging costs, Gross said.

“That is correct,” Bergin said. “The town would provide the hydrological survey that’s necessary for us to determine the depth of the dredge, should it proceed, and we would offset the cost of the permit process and submit the permit on behalf of the property owners.”

The biggest expense for a dredging project is the mobilization of equipment. The second biggest expense is permitting, she said.

But before the survey and permit work is performed, Bergin said a commitment from the residents is needed because the township does not want to spend $60,000 for a project that never goes forward because the residents would have to commit to paying for the dredge work.

Gross said he is aware that the Army Corps had completed eight dredging projects at the entrances to lagoons on Long Beach Island. Bergin said the administration has used that project to re-engage the DOT in a conversation to do the same in Brick Township.

“We’re saying there’s got to be a way when these guys are out here working on projects they can come in and do some of these little ones. Is that going to mean a cost to the township? Maybe, but tell us what that is, so we could make an educated decision on if we could help those people,” Bergin said.

Another resident from Lagoon Drive West, Ihor Huk, said he and his wife moved to Brick two years ago because of his affordable lagoon front property.

“We’re paying about twice the taxes of a house of similar size directly across the street,” he said during public comment. “Some of that money should go towards maintaining the lagoon. We personally had more than $4,000 in damages to our boat the past two seasons. In low tide there is two feet of water, you could walk across.”

John O’Donnell of Lagoon Drive West said it would be a hardship for many of the residents there to pay for dredging.

He said of the 23 houses along the lagoon, four are not livable because of Sandy damage; one is in foreclosure; and a couple of homes are occupied by people who are “very elderly, living hand to mouth. If we’re going to be asked to come up with $7,500 or $10,000 apiece? Do you really think we’re going to get them to fork over that much money?”

In an email, township engineer Elissa Commins said the township has several neighborhoods that have asked for assistance in getting the lagoons dredged.

“These requests go as far back as 2009, with only one that has claimed it silted in as a result of Sandy, which is Nejecho Beach,” Commins wrote.

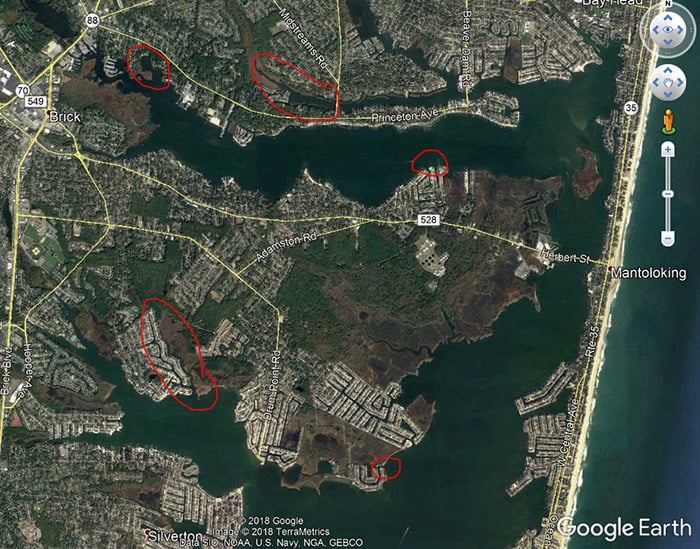

Other areas that have asked for dredging assistance prior to Sandy include Long Point Lagoon, Superior Lagoon (the entrance to Seawood Harbor), the south branch of the Beaver Dam Creek and Perch Creek, she said.

“The bathymetry of the bay and its lagoons changed with Sandy. There was so much sand from the ocean and debris from the storm surge,” Commins wrote.

She said it is important to note that when she refers to the term “lagoon” she mean a natural entrance lagoon that services a community and not the man-made bulkheaded lagoon that provides the rear property line of individual homes.