JERSEY SHORE – In classrooms across Monmouth and Ocean counties, and in schools beyond the Jersey Shore, teachers are entrusted with far more than academics. They hold authority, influence, and daily access to children whose families trust that school is a safe place.

That belief has been repeatedly shaken.

Over the past several years, a growing number of educators along the Jersey Shore have been arrested, charged, indicted, or convicted for sexually abusing students. The cases span multiple districts and grade levels and involve both male and female teachers.

What has also emerged, experts say, is a persistent double standard: when the accused teacher is female and the student is male, public reaction often shifts, minimizing the harm or dismissing the victim altogether.

The case of Julie Rizzitello, a former Wall Township High School teacher, underscores how public perception can shift when the accused educator is female.

Rizzitello, 37, of Brick, pleaded guilty to two counts of second-degree sexual assault, admitting to sexual encounters with two male students, according to the Monmouth County Prosecutor’s Office. Investigators said the conduct involved different victims in multiple towns over several years. She faces sentencing on February 11, 2026, when prosecutors are expected to seek a 10-year prison term, mandatory Megan’s Law registration, lifetime parole supervision, and a permanent ban from public employment.

Despite the guilty plea, public reaction revealed a troubling recharacterization of the abuse. In online discussions, some questioned whether the boys were victims at all.

“It’s the stuff high school boys dreams are made,” wrote one commentator. “And since a female can’t force a male to have sex, then they were more than willing participants. It’s not the same as a male teacher having sex with a young girl.”

Experts say such views ignore the law and the power imbalance inherent in teacher-student relationships, where consent is not possible regardless of gender.

The prosecution of a 44-year-old Jackson resident, formerly a special education teacher at Freehold Intermediate School, is another case in which the accused educator is female and the alleged victim is male.

Allison Havemann-Niedrach is charged with multiple serious sex offenses, including sexual assault, endangering the welfare of a child, and official misconduct, stemming from allegations that she engaged in an illegal sexual relationship with an eighth-grade student while employed in the Freehold Regional School District.

According to court records and statements placed on the record, the state’s case includes over 25,000 text messages and photographs that investigators describe as explicit.

Prosecutors placed a plea offer on the record that requires Havemann-Niedrach to plead guilty to a reduced charge in exchange for a recommended 12-year state prison sentence, along with mandatory parole supervision and sex offender registration. Havemann-Niedrach is due back in court on January 21, 2026, to decide whether to accept the plea offer or move forward to trial.

Why Gender Changes The Narrative

Experts say this disparity is rooted in long-standing cultural myths.

Research published in peer-reviewed journals including Archives of Sexual Behavior shows that male victims of educator sexual abuse are less likely to be believed and less likely to report abuse. Cases involving female perpetrators and male victims are more frequently minimized by peers, families, and even institutions.

Boys are often socialized to interpret sexual attention as a marker of success or maturity. Female educators are less likely to be perceived as capable of predatory behavior. Together, those assumptions distort how abuse is recognized and discussed.

Scholars emphasize that the power imbalance inherent in teacher student relationships does not change based on gender. Minors cannot legally or developmentally consent to sexual relationships with authority figures. The harm does not lessen because the perpetrator is female.

Studies also show male victims are less likely to receive counseling and more likely to experience long term effects such as depression, substance abuse, and difficulty forming healthy relationships.

Male Educators And Clear Condemnation

When the accused educator is male, public response tends to be swift and unequivocal.

In Middletown, former girls basketball coach and physical education teacher Justin McGhee pleaded guilty to sexually assaulting a student under his supervision. Prosecutors described encounters that occurred outside school but within the context of his authority. The state is expected to seek a five-and-a-half-year prison term, along with mandatory sex offender registration and lifetime parole supervision.

In Manchester Township, former high school teacher and varsity basketball coach Ryan Ramsay was charged with sexual assault stemming from allegations involving a student in 2012. The case was filed more than a decade later, underscoring how long it can take victims to come forward. Ramsay was approximately 32 at the time of the alleged sexual relationship. The victim was 17.

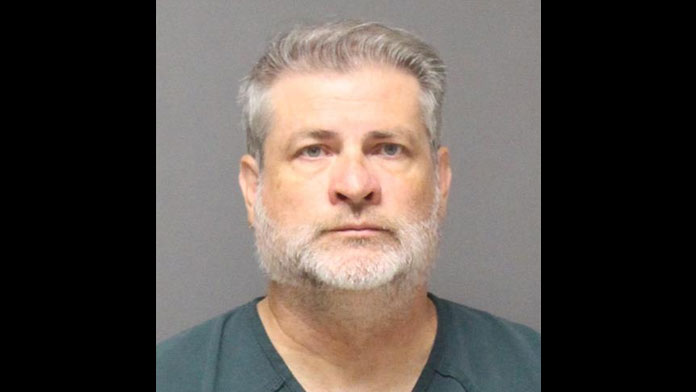

At the Ocean County Vocational Technical School, former performing arts teacher Douglas Bollinger admitted to inappropriate sexual contact with a student. He was sentenced to parole supervision for life, permanently barred from public employment, and required to register as a sex offender.

In another Ocean County case that has expanded across multiple jurisdictions, Darnell Williams, 34, of Manchester Township, was indicted by an Ocean County grand jury on child sex charges tied to alleged abuse spanning more than a decade. Prosecutors allege the abuse occurred between 2010 and 2013 in Manchester Township, while additional charges include accusations of inappropriate sexual contact with a minor between 2020 and 2023 in both Manchester, Stafford and Atlantic County. Authorities have said the investigation widened as additional allegations surfaced, resulting in multiple counts that include sexual assault, endangering the welfare of a child, and official misconduct. The case has underscored concerns about how educators and youth-serving adults can move between districts and jurisdictions, and how misconduct can remain hidden until victims feel safe enough to come forward.

In each of these cases involving male educators, public outrage was immediate and sustained. The students were widely recognized as victims.

A System Under Strain

New Jersey has taken steps to address educator misconduct, including its so-called “pass-the-trash” law, which aims to prevent school employees with substantiated abuse histories from quietly moving between districts.

But enforcement challenges remain, particularly when allegations do not surface until years later or when early warning signs are dismissed.

Experts emphasize the importance of training educators and administrators to recognize grooming behaviors, creating safe reporting pathways for students, and fostering cultures where allegations are evaluated based on facts, not gender expectations.

For Ocean and Monmouth counties, the growing list of cases represents more than a grim tally. It is a call to confront uncomfortable truths about trust, power, and perception.

Abuse does not wear one face. It does not follow one script. And it does not become less harmful if it defies stereotypes.

As courts continue to process these cases, families and schools alike are being asked to reckon with a difficult reality: protecting children means believing them, no matter who stands accused.