TOMS RIVER – The haunting echoes of World War II reverberated through the Toms River branch of the Ocean County Library as Holocaust survivors Gela Buchbinder and Mona Ginsburg shared their harrowing experiences with over 100 stunned attendees.

The event, the fourth in the “Combatting Hate” series, offered a stark reminder of the horrors inflicted upon millions during one of history’s darkest chapters.

Both women, now residents of the same Toms River senior village, were mere children when the world erupted into chaos. Their stories, while different in detail, share a common thread of unimaginable suffering and resilience.

Gela Buchbinder

At 99 years old, Gela Buchbinder is a tiny woman with a spark of feistiness that likely helped her survive as a teenager. Her life, as part of a family of six, took a dramatic turn in 1939 when the Nazis invaded their hometown of Sosnowiec, Poland. Gela was only fourteen at the time.

“The first thing they did was round up all the Jewish men, whoever they could find,” Gela recounted. “Unfortunately, they found my father.”

Gela vividly described how the Nazis marched the men a distance and ordered them to lie face down before opening fire with machine guns. Finally, the firing stopped, and everyone assumed all the men were dead. Three had survived the gunfire.

“The soldiers walked over to the men who they thought were alive and hit them over the head with big heavy boards,” continued Gela. “The German soldiers were laughing, and they appeared to celebrate.”

“Mama and the other women were scared. I was praying and crying,” she said, recalling the terrifying scene.

Gela witnessed another act of savagery when an SS soldier seized a tall, bearded man and yanked off his beard. These were the young teenager’s first encounter with the Nazis – to be followed by personal torture.

The morning after their arrival in Sosnowiec, the German soldiers took ominous pleasure in setting the synagogue on fire. They cheered, stamped, and jumped with glee as they watched the sacred building engulfed in flames.

Ultimately, the soldiers came for Gela at her home in the early hours of the morning, guns drawn. They shouted at her to get out of bed and dress immediately, threatening to shoot her if she didn’t comply.

Gela was taken to the high school, where she encountered other terrified and crying children from her school. They were all shoved, pushed, and beaten by the Germans. Overwhelmed and in tears, Gela found a corner on the floor to curl up in for the night.

“In the morning, a doctor checked us over,” said Gela. “And, in the night, we were pushed in cargo trains like animals and sent to Czechoslovakia.”

Life In The Camp

Gela said that some of those from her hometown were taken to Auschwitz, which she described as a “killing camp.” Gela and the other young women were assigned to a “working camp,” and subjected to forced labor in a linen factory for 16-hour days.

There were 40 girls crammed into one room. Every morning at five o’clock, they had to stand at attention and listen to a speech. The girls were told that the plan was to kill all the Jews, but if they worked hard, they might be allowed to leave, along with their parents. The girls believed this promise, clinging to the hope that it might be true.

“We thought the Germans would not lie,” said Gela. “But unfortunately, they lied.”

Gela recounted the daily horrors she endured, including beatings, starvation, and cruel name-calling. She remembered one instance when her machine broke down and a towering, high-ranking SS officer threatened her.

Overwhelmed with fear, she listened as he snarled in German, “Small devil, I will hang you and then shoot you.”

Despite her terror, the young teenager defied him, telling him he could shoot her and then hang her if he wanted. It made no difference to Gela.

She told him – “If you want to shoot me, then hang me.” She didn’t care about whether she was alive or not.

At one point, someone who maintained the machines took pity on Gela and left her a tiny piece of bread. By the time she was 18, Gela weighed only 56 pounds, her body reduced to skin and bones. She had no food, wooden shoes, and sparse clothing.

One of the worst acts of humiliation came was when the soldiers came through the camp with Dr. Josef Mengele. The girls were told to make a circle and stand in it naked. They were crying, scared, and ashamed.

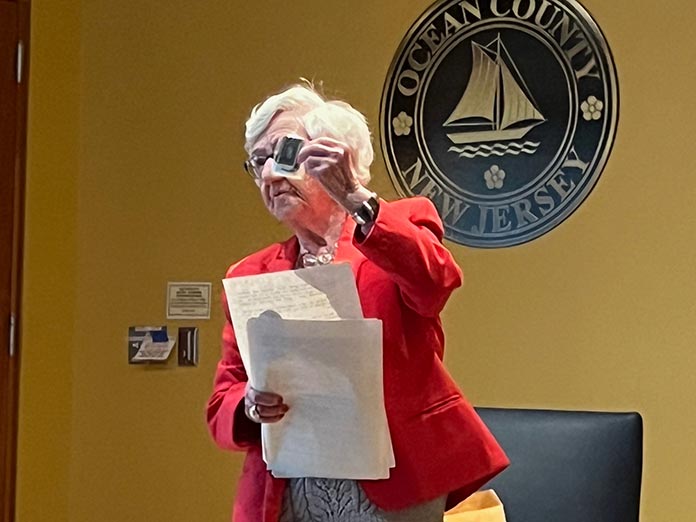

During her presentation, Gela held up a tiny picture that was her only remaining treasure from the horrific days before she was freed by the Russians. Gela had managed to hide a small photograph of her parents and family under the heavy machinery she was forced to operate.

Mona Ginsburg

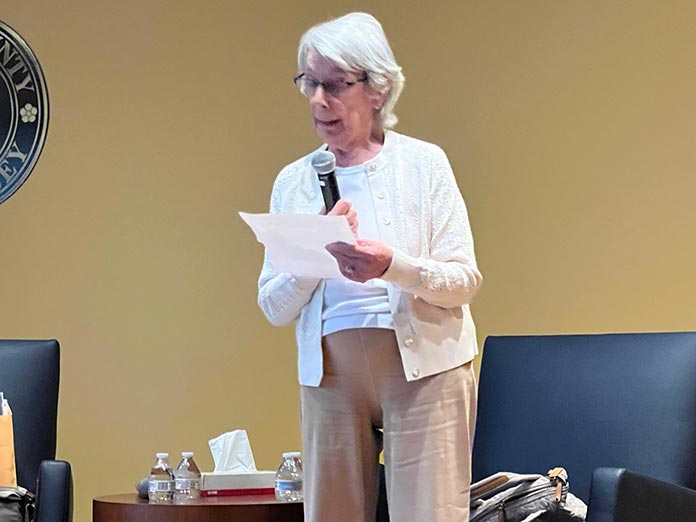

Born in Vienna, Austria to Polish parents in 1933, Mona Ginsberg was just five years old when her childhood erupted into a state of uncertainty. Now 90, Mona’s story is one that speaks of the goodness in people, even when confronted by evil. Her kind eyes and warm voice radiated with gratitude during the presentation,

“Life was still possible for the Jews at that time in Vienna, although it was not good,” shared Mona. “My parents had left Poland because life was already very bad for the Jews.”

The decision to leave Vienna came in 1938 when a brick was thrown through the family’s apartment window and landed on the bed.

“I remember the look of horror on my parents’ face,” Mona said. “They decided to flee – my parents, my uncle and grandmother starting to walk with us through a snowstorm. My father carried my 18-month-old brother in a knapsack.”

Children were not permitted to cross the border. Consequently, Mona’s grandmother, her brother, and she were placed on a train to Belgium. They stayed with relatives in Antwerp until Mona’s parents joined them. Once reunited, the family established a new home in Antwerp.

The history books identify Antwerp as one of the hardest-hit cities in Belgium during World War II. Mona’s family was forced to leave as refugees because they were no longer welcome.

“We moved to Liège, another city in Belgium,” shared Mona. “We also had relatives there and set up home again.”

“I was registered in school as a six-year-old and made to wear the yellow star,” Mona continued. “I felt embarrassed in front of the other children.”

Hiding In Plain Sight

In 1942, Mona’s parents learned from the bishop of Liège that Catholic convents were offering refuge to Jewish children. Mona was placed in a home for poor Catholic girls, while her five-year-old brother was sent to live at a home in Banneux that had taken in Jewish boys.

“The whole village knew I was Jewish because I wasn’t baptized,” said Mona. “When I went to church, I couldn’t take communion. I went to confession with the priest, but it was all make believe.”

“My mother had said to me to never forget that I was Jewish,” Mona added. “It’s stuck to me to this day.”

When the Nazis began arresting Jews, Mona’s father was sent to Auschwitz, where he was ultimately worked to death. Mona’s mother was not home at the time. Realizing the danger, she went straight to join her son at the home in Banneux.

“The home was run by German nuns who took my brother and her in,” said Mona. “They were very courageous people.”

Mona emphasized that the threat of death was not only to her family. Those who rescued them also risked their lives for hiding Jewish people. Both children were even enrolled in school, which was another act of bravery.

Both Mona and her brother easily became attached to the families who took such good care of them. Mona remains close to the generations that followed in the household that took her in.

After the American Army liberated the country in 1945, Mona’s mother set up a new home and took back her brother. When her mother found a bigger place, Mona joined them.

“At first I didn’t want to go back to my mother,” admitted Mona. “I felt embarrassed to leave the family that sheltered me.”

A Shared Hope

Despite the trauma they endured, both women find solace in sharing their stories, hoping to educate and create empathy among future generations.

“I was debating with myself about how to describe all the hardship I went through,” said Gela. “But as painful as it was, I feel we need to talk about it so that hopefully it will never happen again.”

Mona added, “There is hope for the world because there were good people who risked their lives to save Jews like me, and my mother and brother.”