OCEAN COUNTY – Superstorm Sandy wasn’t the first weather event that flattened shore homes, destroyed infrastructure and created new inlets on the barrier island.

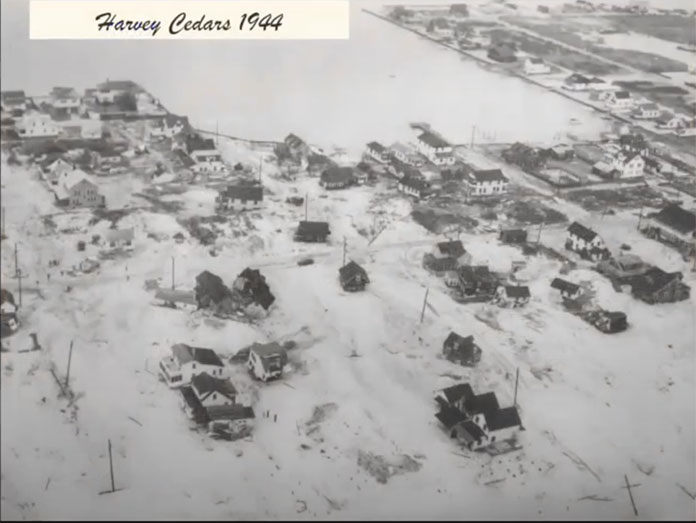

Oldtimers recall a September 1944 hurricane that inflicted great damage to Long Beach Island, Ocean City, Atlantic City and Cape May, including the destruction of bridges that connected towns to the barrier island.

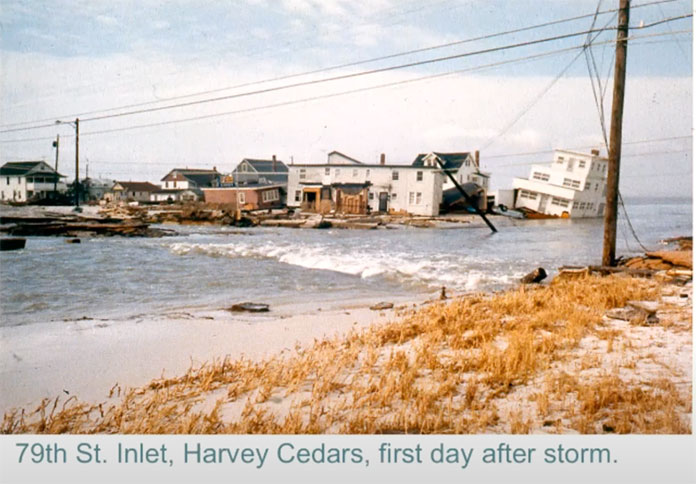

Harvey Cedars was “ground zero” for The Great March Storm of 1962, one of the ten worst storms in the United States in the 20th century, that killed 40 people and caused hundreds of millions in property damage in six states.

These storms and other weather events have been documented in the book, “Great Storms of the Jersey Shore,” now in an expanded 2nd edition that includes a chapter on Superstorm Sandy.

The book was the topic of a recent “Meet the Author” zoom event, hosted by the local environmental group, Save Barnegat Bay. Two of the authors, Margaret Thomas Buchholz and Scott Mazzella, were on hand to discuss their award-winning book.

The authors were introduced by Graceanne Taylor, who is the education and outreach coordinator for Save Barnegat Bay.

Taylor gave some background information on Barnegat Bay, which is the largest body of water in the state of New Jersey. At about 42 miles long, the bay runs from Bay Head to Little Egg Harbor, and only averages about six feet in depth.

The bay has three sites where it meets the ocean: the Manasquan Inlet in the north, the Barnegat Inlet in the central area, and Little Egg Harbor Inlet in the south.

Author Buchholz was born and raised “20 feet from the bay” on Long Beach Island and experienced many of the storms that are chronicled in the book from the time she was a baby in 1935.

As the former editor and writer at The Beachcomber newspaper, Buchholz said that when she and Larry Savadove wrote the first edition of the book 30 years ago, “we thought it was a good time for a storm book because nobody had done it, encompassing the whole coast.”

During her research, Buchholz learned that barrier islands “want to move,” and over a period of thousands of years they inch their way towards the mainland.

Long Beach Island has been mostly stabilized, she said, but the southern tip, Holgate, is a state park and has not been stabilized.

“You see how the natural movement of the island goes to the right,” Buchholz said. “Holgate has moved like a dogleg and then stretches out again.”

Author Mazzella is currently a history teacher but was formerly a journalist who also worked at The Beachcomber newspaper.

He said he grew up during a period of “peaceful weather,” and did not experience most of the storms he wrote about.

The Jersey Shore is located next to the “Hurricane Highway,” along the Atlantic seaboard, Mazzella said. Most of the storms don’t make landfall and go out to sea.

There were far fewer homes at the shore before the Garden State Parkway opened around 1950, but once it did, the barrier island filled with people and houses, and real estate values went through the roof, he said. Beaches filled up and businesses developed.

For several generations, people got used to not having big storms, and certainly nothing like Sandy, he said.

“Ask anyone who’s been at the shore for a long time and they’ll tell you, you need to watch out for the nor’easters as much as any hurricane,” he said. “Nor’easters are sneaky, and their forecast is not as far ahead of time as a hurricane, usually, and they can do a lot of damage.”

Mazzella said that storm watchers were convinced that Hurricane Irene in 2011 would be “written in the history books.” Shore residents were told to evacuate, and while it did cause some local flooding, most of the damage was in northern and western Jersey where there was copious amounts of rainfall and flooding.

That’s a problem, Mazzella said, “because everyone gets worked up, everybody does the right thing, evacuates, and it’s not what they thought,” he said. “So when Sandy came around the following year, it was hard to convince people to evacuate.”

Sandy’s track was different from the tracks of previous storms in that it tracked perpendicular to the shoreline. The storm was over 1,000 miles in width and had one of the biggest cloud canopies of any tropical system in history, he said.

Because of its huge size, and because it had developed into a nor’easter-type storm and was no longer a hurricane, it became like a “super storm,” which is where that term came from, Mazzella said.

Superstorm Sandy’s landfall center was Brigantine, but ground zero was Mantoloking, where a new inlet formed at the base of the Mantoloking Bridge.

During this past summer, the center of Tropical Storm Fay came in at the southern tip of Long Beach Island, the same spot as Superstorm Sandy and Tropical Storm Irene.

“We had three tropical systems in less than a decade come in, in almost the exact same spot in New Jersey,” he said. “It just blows my mind that we could get three storms in that same spot.”

Mazzella said he believes the lesson that needs to be learned is people have to know the impact of storms, when most only remember their own last experience.

“Like with Irene – that wasn’t a big deal for a lot of people at the shore, so they went into Sandy thinking about Irene,” he said. “When they say evacuate, evacuate. You could always fix stuff, but you can’t fix a life lost.”