BRICK TOWNSHIP – A legend has passed.

Warren Wolf, whose career as the head coach of the Brick Township High School football team was chock full of championships, died of natural causes Friday at the age of 92.

Sam Riello, who was Wolf’s first star running back from 1958-61, confirmed the death Friday night during the NJSIAA Rumson-Fair Haven Regional-Wall Township playoff game, the website reported. Wolf died at the Jersey Shore Medical Center in Neptune.

According to Riello, Wolf’s son, Warren Charles Wolf, who played and coached under his dad, texted friends, saying simply, “Dad’s in Heaven.”

Riello, who coached under Wolf for many seasons, officiated numerous high school football and basketball games and enjoyed a career as a Brick educator.

Wolf, who guided the Green Dragons to a 361-122-11 record in 51 seasons, announced his retirement as the state’s career wins leader at a Dec. 1, 2008 ceremony/press conference at his beloved school. He stepped down at the age of 81. He was the first on-the-field coach in the history of the school, which opened in 1958.

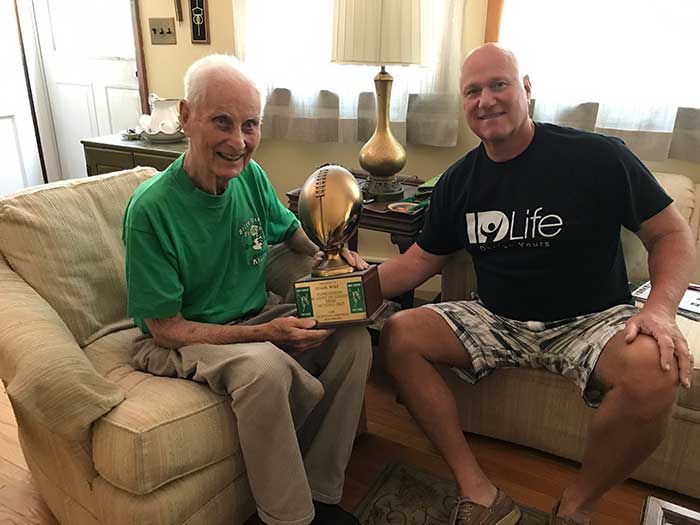

Asked at his Brick home by jerseyshoreonline.com and The Brick Times in a June 22, 2017 interview why his teams were so successful, Wolf said with a laugh, “No one man can do it alone unless he’s Johnny Weissmuller,” referring to the Olympian champion swimmer.

Wolf looked back at his career.

“I remember every detail of my career because football is my life and has been my dedication,” Wolf said on nj.com at the gathering. “My wife, Peggy, came before football and football came before everything else. It’s been a marvelous 51 years. I saw so many of my friends today. So many of my boys are still in contact with me. I think it’s time they had new leadership. I’m going to step back now and do things I want to do when I want to do them.

“Nothing ever gets in the way of football and that’s what I expected from my boys and my coaches.”

Wolf returned to the sidelines in 2010, coaching the Lakewood Piners to a 3-7 record. Lakewood snapped a Shore Conference-record 33-game losing streak in 2010. Wolf coached his last game Thanksgiving Day against host Toms River South. Lakewood bested the Indians in sleet and rain and his Piners briefly placed their beloved coach atop their shoulders in triumph.

Known as the Silver Fox because of his hair color, Wolf led Brick to six NJSIAA sectional titles, eight undefeated seasons, 42 winning seasons and 31 division titles (25 in the Shore Conference).

“We had a lot of success and it takes good players and good coaches to have success,” Wolf said. “We had a lot of boys who liked to play football. We were one high school at the time I came down here.”

Brick won the first sectional title game played in history. It captured South Jersey Group IV with a 21-20 win over Camden at Atlantic City Convention Hall.

“It was our most meaningful title,” said Wolf, whose son, Warren Charles, started at offensive tackle for Brick in the game. “It set the tone. Our boys realized that by working together they can come up with a championship.”

Wolf went out a winner at Brick. His last game was a 34-27 win over Brick Memorial that finished a 6-4 season and earned the Green Dragons a share of the Constitution Division title.

Wolf brought prominence to Brick, at one time a small Ocean County town. Numerous families moved to Brick to enable their sons to play for Wolf. Landmarks in his career include a two-touchdown win at traditional state power Phillipsburg in 1966 and a victory over his idol, Joe Coviello of North Bergen, at Jersey City’s Roosevelt Stadium in 1970.

“We sent 22 school buses to the Phillipsburg game,” Wolf said. “After we beat North Bergen, people knew who Brick Township was and people started moving here. We went from 26,000 to 90,000 people and I like to think football had a little something to do with the growth of Brick Township.”

Wolf surpassed Coviello’s state record of 252 victories in 1992 with a Friday night win over host Southern Regional. Coviello praised Wolf to the heavens to the Green Dragons in their locker room after the contest.

Wolf worked lots of Coviello’s strategy and training techniques into his methods while coaching as an assistant under his mentor at Memorial of West New York.

“He was a master coach and he knew what he wanted to do,” Wolf said prior to turning 90. “He never followed the same pattern. Coach Coviellio taught me that you don’t win it on the drawing board. He said, ‘You win it on the field.’ As coaches, we made the practices harder than the games. We had a large number of boys on our teams. Some never got to play much in the games, but they enjoyed our practices.”

Wolf attended numerous clinics during off seasons to avoid being stereotyped by opponents. He soaked up knowledge at such places as Penn State under the legendary Joe Paterno, Texas A&M, Arkansas, West Point, Houston, the United States Air Force Academy, Nebraska and Pacific Lutheran.

“You find out how nice the people are,” Wolf said. “They immensely helped me. I went each spring to learn how they do things. I would always ask myself, ‘Can I do it at the high school level?’ I tried not to coach over my head. The more you go to different schools, the better you get. You have to learn what you can do with your players and you learn it in a hurry.”

Warren Charles Wolf spoke highly of his father.

“Dad was always learning,” Wolf said. “He never took anything for granted. He always knew there was something else that would make a difference. Learning kept him sharp. He always wanted to learn something new. If he went somewhere and learned one thing, it would be worthwhile. We instituted a magnetic board on our sidelines, an idea we got from Pacific Lutheran, an NCAA Division III school.”

Wolf was the deputy superintendent of the Brick Township School District, supervising its summer school. He served as Mayor from 1971-75, a councilman from 1982-93, an Ocean County Freeholder from 1975-81 and a member of the state’s General Assembly as a Republican from 1981-83. He was elected to the New Jersey Sports Writers Association Hall of Fame in 2008.

Wolf, who considered legendary late Penn State coach Joe Paterno as a close friend, was the planter of what many termed the Shore Conference Coaching Tree as he groomed such coaches as the late Vic Kubu (Manasquan), Ron Signorino (Toms River, Toms River South), Ron Signorino Jr. (Toms River South), Rob Dahl (Brick Township), George Jeck (Toms River East), Al Saner (Point Pleasant Boro), Dennis Toddings (St. Joseph of Toms River, now Donovan Catholic), Dan Duddy (Central Regional), Jim Calabro (Brick Memorial), L.J. Clark (Lakewood), Steven Filippone (Daniel Hand High School in Connecticut), Mark Heil (who coached at a North Carolina high school), current Brick Township coach Len Zdanowicz, Tim Osborn (Jackson Liberty), Don Ayers (Middletown North), Don Reid (Brick Memorial) and Bob Auriemma, who retired as the state’s career wins leader among ice hockey coaches. The latter coached the Brick Green Dragons.

Wolf nurtured lineman Art Thoms, who starred for Syracuse University and the Oakland Raiders. Former Brick Township standout Pete Panuska is the school’s athletics director.

Signorino served as an assistant coach under Wolf, guiding the linebackers. Duddy, Calabro and Jeck were Wolf’s assistant coaches. Auriemma was an assistant under Wolf, who founded the ice hockey program.

Prior to the opening of Brick Memorial, Brick often dressed more than 100 players for varsity games. The school was known as the University of Brick because of its large rosters, punishing ground assaults, led by the feared Brick Sweep, and stingy defenses.

Wolf, who served as an elder in his church, was humble in victory.

“All glory goes to God,” he often said.

He blamed himself in defeat.

“The problem was my coaching,” he often said.

He was an admirer of swift Ocean Township running back Ed Conti, who played well against the Green Dragons in an Ocean victory.

Asked to assess Conti’s performance, Wolf said with a smile, “There he goes.”

After wins, Wolf stood on a bench in the locker room and handed game balls to his team’s best players, delivering inspiring speeches.

An avid fan of the Chicago Cubs, Wolf ended the speeches with, “Let’s go Cubs,” when the team played well.

Two of his favorite sayings were, “Our future is in front of us,” and “Time will tell.”

Wolf was known for coaching the Green Dragons in a gray suit and brown shoes for decades. He often wore the outfit during the Green Dragons’ biggest games.

He enjoyed snow skiing and playing golf, and rang the bell for the Salvation Army during the Christmas season for charity at Brick shopping centers.

Asked if he would return to coaching as he became older, Wolf said, “As long as I have my health and if the board of education will have me.”

Wolf often dashed onto the field with his players prior to games and at the start of the third quarter as their fans roared their approval.

Signorino unleashed cartwheels after wins while coaching at Toms River, South and Brick. He missed a Brick game because of an illness and Wolf, who was in his 70s, performed cartwheels after a win in the locker room in a tribute to his buddy, igniting a deafening roar from his Green Dragons.

Wolf gave stirring pregame speeches at all times. However, he had a little more passion when Brick went against South in their bitter rivalry.

“Remember, you are Brick Township boys,” he’d say. “Remember what you represent. If it wears a maroon jersey, hit it, but you must do so within the framework of the referee’s whistle.”

Wolf said his wife, who he often referred to as, “My dear wife, Peggy,” played a large role in his success.

“She was very understanding,” he said. “She knew when we won. She knew when we lost. She knew when the boys would come to our (Brick Township) house to look at tapes of our games. She was my right hand. She missed two games in my first season at Brick and one in my second year at Brick. She was the most important person. She learned the game. She was always my girl. My claim to fame is that I married a cheerleader.”

“If we lost, I would say, ‘Sorry about that,’ ” said Mrs. Wolf, who was a Memorial cheerleader. “If we won, I would say, ‘Congratulations.’ ”

Wolf summed up his beloved sport, stating, “Football is a great sport, but it’s either hit or get hit. The choice is yours. It doesn’t matter how big you are. If you can run like a scat back…you can’t teach running, but you can teach blocking.”

Duddy’s reflections: One of Wolf’s biggest admirers was Duddy, who played quarterback under Wolf from 1972-74. With Duddy as an assistant, Brick won three straight South Jersey Group IV titles during the early 1980s.

“Coach Wolf was so successful because of his intensity and communication with his coaches and players,” Duddy said. “He had extremely high expectations. He was demanding. And yes, off the field he showed love. He knew who we were, what we were doing off the field – he had social scouts – and he demanded that we always be gentlemen. He demanded much from his coaches. They were very loyal to him because he always respected them and raised them up to us. He injected an amazing pride in us. He was constantly fostering tradition, much of that, I came to know, was based on his superstitions.”

Duddy said practices were intense.

“Coach Wolf coached with a severe urgency and impatience on the practice field,” Duddy said. “He was a great motivator/politician on the field, not a BS-ing politician. He knew how to handle people and make them produce. He put kids where they belonged on the field and made us feel great about it. I was the starting quarterback each day of my junior and senior years (Brick was considered one of the state’s top five teams by the Star-Ledger of Newark). However, he made me feel like I was fighting to keep my job each day of the week.

“Game day was easy. He also believed so much in repetitions and l-o-o-ong practices. It was torture, but on game day I would hear the play called by the coaches, take the snap and throw the ball. Our band was playing our touchdown fight song with me celebrating on the sideline without even thinking about it. We were automatic. It was expected. Done deal. We were so well coached to succeed – almost robotically.”

During Duddy’s time as a varsity player, Brick suffered only one loss, falling to Montclair during his senior year.

“It would have been our second straight state title if we had won,” Duddy said. “The game ended early due to a brawl that included fans and players. (Brick’s) Mark Heil was on his way into the end zone with an intercepted pass, but was tackled by a Montclair assistant coach from the blindside. We were given eight points. The refs ran out. Cops came on the field. The eight points were not enough. We won all of the conference titles that were available that year.”

Duddy coached under Wolf from ages 22-32 (1978-87).

“Practices were even longer from the vantage point of an assistant coach,” Duddy said. “I learned about him from a different perspective because I started coaching with the staff that coached me. The staff had a sense of humor when coach Wolf wasn’t around so that they could get through the laborious work. The staff loved him and respected him. When coach Wolf entered the coaches’ room, any joking or horseplay was immediately stopped. We spent many, many hours in the film room. He expected our position groups to know what they were doing assignment-wise and put it on us coaches – not the players – to take responsibilities in being great teachers.

“As fiercely focused and demanding as he was, he would floor us once in a while with a sense of humor. We hated going to the chalkboard to explain something or give a scouting report. He challenged us endlessly. It is still one of the most difficult things I have ever done. He always believed in celebrating with the staff at the local pub with a burger and a beer. The first round was traditionally bought by him and we all raised the glass to coach Wolf, loudly saying, ‘Here’s to Brick!’ “

Wolf had numerous sayings.

“He’d say, ‘shake it off’ after a Brick player was a little banged up,” Duddy said. “After just about every single play, he’d say, ‘Get up!’ He cussed when he said, ‘Cheese and crackers. Crimony!’ ” When he was really mad, he’d say, ‘Jumpin’ Jiminy crickets.’ To get us to respect our upcoming opponent, he’d say, ‘Who do you think we are playing this week, Secaucus Prep?’

“His other sayings were, ‘Hit or be hit. You are only as good as you are today. If you are not ready to hit, you will find yourself in an ambulance. If you see a (opposite color jersey) shirt standing around, knock his block off! Boys, this is the greatest half of your lives. When the going gets tough, the tough get going. Boys, buckle up your bootstraps. We are going to war. Do your jobs or go home. Stop thinking.’ “

Prior to the opening of Brick Memorial, the Green Dragons – 100-plus strong – often stormed onto home and away fields with Wolf leading the way with a sprint.

“I believe we dressed 106 players for my junior year when we played Phillipsburg,” Duddy recalled. “We had to run single file down a hill from their locker room. It was truly awesome in the true sense of the word, awesome, for any team to see that. Looking back, coming onto the field for away games in single file was done purposely in those days for that reason. Some kids wore practice jerseys numbered over 100. The crowd noise was deafening. The University of Michigan fight song was our song. Still gives me chills.”

Asked if he was superstitious, Wolf had said, “I think superstitions are silly. They are the work of the devil.”

However, to hear Duddy tell it, Wolf was plenty superstitious.

“He passed out Wrigley’s Spearmint gum to every Brick player during the pregame stretch,” Duddy said. “My job as an assistant coach was to get the gum every game day from the athletic director’s cabinet. One day, there was Wrigley’s peppermint. When I gave it to him, he became very upset and told me I had very little time to get it fixed. I went to 7-Eleven and thanks be to God I bought enough for the team. I never asked to be reimbursed.”

Wolf was a big believer in music.

“The songs of the University of Michigan was played every game in our locker room,” Duddy said. “It was a vinyl album that skipped in many places. My job was to put it on and move the needle for every skip. To this day, I can tell where that album skipped, on what songs and on what parts of the songs.”

Wolf spoke to his players on a personal level after each game.

“He stood by the locker room door to say something personal to every player when we left,” Duddy said. “He’d say, ‘Pick up your grades. Tell your parents I said hello. Get a haircut.’ He’d never say, ‘Nice game.’ He waved to planes when they flew overhead no matter the situation. He walked onto the practice field and left the practice field from the very same spot. He left the game field after practice on the day before our game after our walk throughs, through around the end zone pylons the same way every week.”

Duddy said Wolf was always the final person to walk off the practice field.

“He would never step off the field before you,” Duddy said. “I once had a conversation with him as we walked off the field. We were way behind the others. I tried to trick him into stepping off the curb first without saying anything. This was all unspoken. He would not be tricked. He was all over it.

“He was always the last out of the building for our away games and would spit out mouthwash onto the parking lot as he walked to the bus, being the last on the bus. He always said before sitting down, ‘Check your mouth pieces. Check your chin straps. Check your laces and check your desire to hit.’ Then, he would sit down. Never a word was spoken on that bus by any of us.”

Wolf didn’t use a lot of chalk when coaching.

“He used the very same chalk and eraser for the chalk boards at away locker rooms or he would not write until we found them,” Duddy said.

Duddy was the head coach of Central Regional in its loss to Wolf’s Green Dragons in a sectional championship game at Brick.

“It was so gratifying to see the class of Brick and Coach Wolf that day,” Duddy said. “They were so welcoming of myself and our team. So classy. I wanted to win so badly. For the first time, I could see all of those flags (denoting each title Brick won under Wolf) from the opposing sideline. And so many fans. I am such a proud Brick guy, but I truly loved the Central kids as they were so tough.

“I still anguish over the loss and how it was so close. Two last-minute penalties helped their win for sure. The disparity of emotions from the two teams at game’s end was so powerful. It was a great game to be in, but we went there to win it.”

During a Central home game in his first season at the helm, Duddy wore a piece of green and white (Brick’s colors) material.

“I actually asked my wife, Maura, to sew it into my right pants pocket,” he said. “It was a piece of my game jersey from when I played. I could stick my hand in my pocket and rub my fingers on it whenever I wanted some of that Brick magic. I was very superstitious, too, like coach Wolf was, but not as much as him, I’m sure. Nobody knew I had it in my pocket. I had Rosary beads in my left pocket. Funny, I rubbed that jersey more than I squeezed those beads. Not sure if that was a good thing to admit.”

Duddy said Wolf invited him to his home prior to becoming Central’s coach.

“It took him about five minutes to do what he wanted,” Duddy said. “He took me into his garage and gave me a handmade ring with a green emerald and a football on it. He said, ‘Danny, just be yourself.’ That was it. It came to unfold over time just how many times a day I would say to myself on the field, ‘What would coach Wolf do?’

“In fact, it was not even said. It was the way I lived. I began to slowly divorce myself from that over time as my players became old enough to join me on my coaching staff. I began to find myself. I wondered and I believe it to be true that his advice was probably centered on his own struggles with departing from coach Coviello.”

Duddy said Wolf taught him to live life with passion.

“Coach Wolf taught me that without a fierce passion for something that serves others we are not truly living,” he said. “I have been known to be a bit too intense with my own children and wife at home, but it’s hard to turn off the switch that is truly founded on love, a love for living, through a love for the successes of others and to maintain leadership. A man needs to lead.

“I am a very passionate speaker to our youth because of Brick football, which is, of course, coach Wolf. I have learned to quash that fierceness when it is not so necessary. I guess I am finally becoming myself. ‘Be yourself,’ is what he taught me the most. And to start doing that right now is what I have learned.”

Wolf took great pride in serving as an Elder in his church.

“Coach Wolf was a solid Christian man,” Duddy said. “I don’t think his urgency, impatience and demands were compromised, but his heart took a different approach in dealing with kids. This is what gave him longevity. He truly loved to coach. He didn’t live to coach. He loved to coach. That practice field was his platform to love, to love like a true man, like a boy needs that love, that real love of a real man. He coached to love. But man, that was one really tough love. I could always count on him.”

Duddy often spoke to Wolf’s staff members.

“I would be the best observer of any changes in his style because I was not there as a personal witness, but I had plenty of Brick brothers on his staff to talk to regularly,” Duddy said. “Coach Wolf was the greatest larger-than-life person in our collective lives and he was always the topic of discussion. What I can remember was that he understood that the culture had changed, boys changed due to the family structure collapsing in our country and that socio-economically there were changes in Brick. There were changes in race, but he operated on love always. It might have changed from the tough love that we always got in my generation to more of an understanding and nurturing love.”

Brinster’s recollections: Retired Jersey Shore journalist Dick Brinster provided his memories of Wolf.

“The first time I laid eyes on Warren Wolf was Thanksgiving Day 1958 as a 12-yer-old kid from Seaside Heights in his first month as a junior high school student at Central Regional. At that tender age, players, coaches, managers and elected officials were almost rock stars in my fertile mind. Today, as I live happily in retirement in Whiting, a section of Manchester Township, Warren is foremost among those I still regard with awe.

“After all, he was a football coach, hockey coach, basketball referee, deputy superintendent of schools, a councilman and Mayor of Brick Township, Ocean County Freeholder and state assemblyman. Those were plenty of hats to wear and for years he wore more than one as he went about the business of establishing himself in my opinion as the greatest man in the history of Ocean County.

“The Man I (Brinster) Call Coach: I had read that he was 29, but I was skeptical when I saw him leading his Green Dragons on the field that Thanksgiving, never dreaming his name would become symbolic with coaching excellence at the high school level to compare with the best in the nation.

“His hair was quickly turning toward the white shock by which he became so recognizable. So I figured that at 29 he must be telling (no pun intended) a little white lie. Fast forward about 40 years from that day and we are at a reunion of those involved in the inaugural All-Shore Classic…the lone high school football game still played in New Jersey each year since 1978.

“As the game’s founder, I was making a few remarks while desperately scanning the crowd for Warren. When I spotted him, he didn’t look a whole lot different than he had four decades earlier.

Ponce de Leon had little on Warren Wolf.

“I found him at the rear of the crowd, thanked him for making the game a success right out of the gate and called him, “Coach.” I couldn’t think of any description more appropriate or respectful.”

Brinster remembers Wolf as an ice hockey aficionado: “As a journalistic pup in the mid-1960s I became sports editor of the New Jersey Courier, a Toms River-based weekly newspaper. A hockey fan, I spent every Saturday at the Ice Palace in Brick. There…his players dressed in football jerseys in the program’s infancy…was coach Wolf pioneering a sport that five and a half decades later is played by nearly 30 schools in the Shore Conference.

“I cannot think of any moment in life where I respected an individual more than Warren one Saturday morning when a full-scale brawl broke out. I recall an earlier time when a Brick player was ejected for fighting.

“How many goals are you going to score sitting over there?” the coach asked.

“On this day, the visiting team whose identity escapes me five decades later was losing and instigating for a fight. When it was over, public address announcer Wolf (yes, he even announced the goals) apologized profusely as the perfect way to end hostilities even though it was obvious someone else should have been performing a mea culpa.

“If there is anything Warren loved as much as his family and the Brick Green Dragons, it’s the Montreal Canadiens. I used to get tickets to Philadelphia Flyers games and most of the time Les Habitants were in town Warren would find a hole in his busy schedule. These were the Canadiens of Jean Beliveau, Henri Richard, Jacques Lemaire, Yvan Cournoyer and Serge Savard.

“Warren always wanted to go down to the ice pregame to talk to the Canadiens. None of those colossal stars was preferred to a little round 38-year-old goaltender named Gump Worsley.

“Hiya, Gumper,” Warren said one day with me within earshot. “Oh, hi coach,” Worsley replied.

“I guess now, in retrospect, I should not have been so surprised.

“On a couple of occasions, we took Warren’s son, Warren Charles Wolf, who at that time must have been about 10 years of age. With every third line change, the father would tell his son, “Warren, watch Gilles.” That would be Gilles Trembley, hardly a Beliveau or Richard, but a poster boy for disciplined, two-way play…Warren’s kind of player.

Brinster recalls the All-Shore Classic: “In 1978, the New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletic Association, the governing body of high school sports in the state, adopted a rule to permit all-star football games featuring graduated seniors sponsored by corporations with proceeds to charities. A handful sprung up and most vanished quickly. The only one that never went away is the one backed recently by the United States Army. The game began as the All-Shore Classic, Monmouth County versus Ocean County, sponsored by the Asbury Park Press.

“As sports editor of The Press, I pitched the idea to the newspaper’s board of directors. More than one charitable pursuit of the newspaper allegedly had not come out in the black. What made me think this would be any different, I was asked.

“I answered in two words: “Warren Wolf.”

We had to delay the start of the game for 30 minutes so the long line of cars could enter Wall Stadium, an auto racing track in Wall Township, from Route 34 that midsummer night. Years later, when I was asked how I knew we would succeed, I answered, “I’d like to say I was brilliant, but it was a no-brainer.” A no-brainer from the moment I made my first call…to Warren…asking him to coach the Ocean County team.

“Dick, I appreciate you thinking of me,” he said. “I would be honored.”

HE was honored?